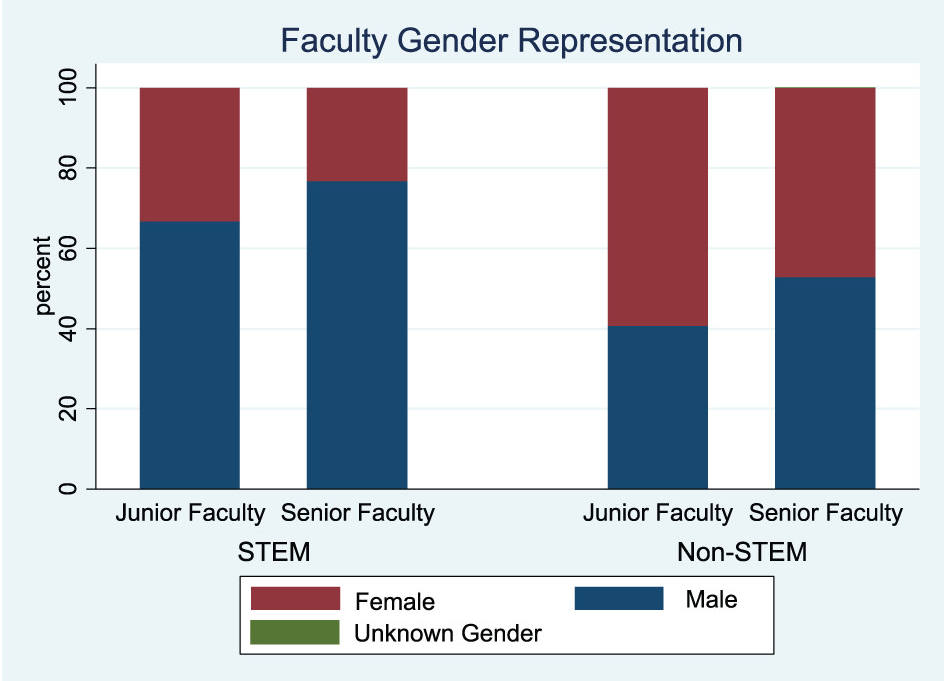

It is the dream of every young scientist; after many agonizing years filled with hard work and perseverance, you are at the finish line. Everything falls into place and you receive the most satisfying email you may ever receive: “We are pleased to announce that your manuscript has been accepted for publication in Nature”. This is the ultimate reward for all the long hours spent in the lab and undoubtedly a sign that your work matters. Of course, Nature is one of the most well-known and competitive scientific journals, so the chances of this scenario actually taking place are low. However, there is a large group of scientists for whom this dream comes true less often than expected: women. In an editorial recently published in Nature1, a summary of recent publication statistics was provided, proving a very salient point: women are very under-represented in the journal’s articles. This includes contributors of commissioned content, referees of scientific papers, reviews, but most importantly, authors of empirical research papers. Specifically, only 16% of corresponding authors in all of Nature’s recent publications are women, which is much lower than the estimated 29% of women in science globally2. A recent study providing the same analysis across multiple high impact-factor journals shows that the higher the impact factor, the lower the percentage of women as first or last authors, with most journals falling below 30%3. Thus, this is far from an isolated problem and it is imperative to figure out why this happens. The first question we should ask is, “when does the problem start”? Is there a specific stage in women’s academic careers that hinders their likelihood of publishing in highly esteemed journals? The answer is that it starts later than you might think. At the very early stages of higher education, women are very much present. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are more women college graduates than men4. This trend continues onto doctoral studies, with women earning more doctorates than men across most scientific fields, with STEM fields being the only ones where they are slightly lagging5. However, this equity quickly starts falling apart as soon as we move on to academic faculty jobs. According to a recent study looking at public universities, women are clearly in the minority when it comes to both junior and senior faculty positions6. The only job categories that have a prevalence of women are lecturer and instructor positions7, which are usually part-time postings with a high turnover rate. Academic tenure is not an easy accomplishment for women either, with only 37% of tenured faculty being women and only 10% being full professors8. The data give us a clear indication as to why it is so difficult for women to publish in high impact-factor journals: it is hard to be competitive in research without a stable job environment. [caption id="attachment_2432" align="aligncenter" width="947"] Faculty representation by field, split by assistant and associate/full professors (Source: Li & Koedel, 2017, Educational Researcher Vol. 46, Issue 7, pp. 343-354 https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726535[/caption] What is the reason that women are less present in high-ranking academic jobs? This is a very complicated topic and by no means restricted to academia. In fact, statistics from industry positions show very similar trends, with women becoming increasingly rare when moving up the job ranks9. Some researchers believe that women are more likely to move away from male-dominated fields because minorities tend to prefer education or work environments where they are among people who share their characteristics10. Another hypothesis is that women pay what is called the “baby penalty” at a much higher rate than men. That is, women that have babies during the early stages of their academic career are much more likely to turn down a future in academia11. Furthermore, having children has been found to highly affect women’s pay, but not men’s12. These give a glimpse into why women are underrepresented in many science-related fields, both in academia and industry. [caption id="attachment_2434" align="aligncenter" width="605"]

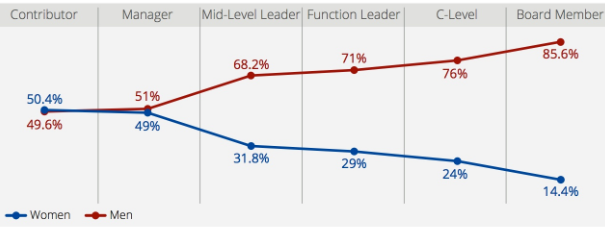

Faculty representation by field, split by assistant and associate/full professors (Source: Li & Koedel, 2017, Educational Researcher Vol. 46, Issue 7, pp. 343-354 https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726535[/caption] What is the reason that women are less present in high-ranking academic jobs? This is a very complicated topic and by no means restricted to academia. In fact, statistics from industry positions show very similar trends, with women becoming increasingly rare when moving up the job ranks9. Some researchers believe that women are more likely to move away from male-dominated fields because minorities tend to prefer education or work environments where they are among people who share their characteristics10. Another hypothesis is that women pay what is called the “baby penalty” at a much higher rate than men. That is, women that have babies during the early stages of their academic career are much more likely to turn down a future in academia11. Furthermore, having children has been found to highly affect women’s pay, but not men’s12. These give a glimpse into why women are underrepresented in many science-related fields, both in academia and industry. [caption id="attachment_2434" align="aligncenter" width="605"] Percentages of women and men in various positions, from companies in the Massachusetts Life Sciences cluster (Source: https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/fortunes-most-powerful-women-list-stresses-gender-gap-in-pharma/505463)[/caption] The evidence paints a bleak picture, but what can we say to the young women scientists that want to thrive against these statistics? During a recent iJobs event about women in academic biology, a panel comprised of accomplished female professors at Rutgers University had a few tips for rising women in academia. These tips are not limited to academia alone and can also be applied to industry positions: - Good time management skills are necessary for juggling career and family life. - Volunteering and networking can provide great opportunities for career development. - Avoid changing your personality to adapt to male-dominated environments. Instead, the key is having more confidence to show your unique skills and thus prove your self-worth. They acknowledged that unconscious bias definitely exists, but they all found a way to surpass obstacles and run successful labs. Overall, there is plenty of hope. In fact, Nature itself is making important progress by recently announcing the first woman editor-in-chief, Dr. Magdalena Skipper, in its 149 years of history13. Progress is being made, albeit slowly. Recent studies show that the gender gap in science is closing in most fields, but it will take many years to reach equity14. Some schools are taking steps towards increasing their female faculty members, with government funds backing these initiatives15. Most importantly, awareness of the issue seems to be at an all-time high. As Emma Walmsley, the first female CEO of GlaxoSmithKline, said16: “We should be much more proactive about sponsoring and supporting all types of diversity to get to the senior leadership positions”. Hopefully, this spirit is slowly prevailing in science. References: 1 Nature 558, 344 (2018). 2 UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Fact Sheet No. 43, 2017 (http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs43-women-in-science-2017-en.pdf). 3 Shen, Y.A., Webster, J.M., Shoda, Y., and Fine, I., Persistent Underrepresentation of Women's Science in High Profile Journals bioRxiv 275362; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/275362. 4 News Release, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, April 26, 2018 (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/hsgec.pdf). 5 Survey of Earned Doctorates, National Science Foundation, June 2017 (https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2017/nsf17306/static/report/nsf17306.pdf). 6 Li, D. & Koedel, C., Representation and Salary Gaps by Race-Ethnicity and Gender at Selective Public Universities, Educational Researcher Vol 46, Issue 7, pp. 343 – 354 7 National Center for Education Statistics (https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=61). 8 TIAA Institute, Taking the measure of faculty diversity, Research Overview, October 2016 (https://www.tiaainstitute.org/sites/default/files/presentations/2017-02/faculty_diversity_overview_0.pdf). 9 ”Fortune's Most Powerful Women list stresses gender gap in pharma”, by Jacob Bell (https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/fortunes-most-powerful-women-list-stresses-gender-gap-in-pharma/505463/). 10 ”Examining faculty diversity at America’s top public universities”, by Cory Koedel (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/10/05/examining-faculty-diversity-at-americas-top-public-universities/). 11 ”The Baby Penalty”, by Mary Ann Mason (https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Baby-Penalty/140813). 12 ”Children hurt women’s earnings, but not men’s (even in Scandinavia)”, by Claire Cain Miller (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/05/upshot/even-in-family-friendly-scandinavia-mothers-are-paid-less.html). 13 ”Nature announces new editor-in-chief”, by Holly Else (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05060-w). 14 ”New study says the gender gap in science could take generations to fix”, by Luke Holman (http://theconversation.com/new-study-says-the-gender-gap-in-science-could-take-generations-to-fix-95150). 15 ADVANCE: Increasing the Participation and Advancement of Women in Academic Science and Engineering Careers, National Science Foundation (https://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=5383). 16 “The first female big pharma CEO had the perfect response to a question about women in leadership”, by Lydia Ramsey (http://www.businessinsider.com/gsk-ceo-emma-walmsley-on-diversity-in-pharma-2018-1). This article was edited by Maryam Alapa

Percentages of women and men in various positions, from companies in the Massachusetts Life Sciences cluster (Source: https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/fortunes-most-powerful-women-list-stresses-gender-gap-in-pharma/505463)[/caption] The evidence paints a bleak picture, but what can we say to the young women scientists that want to thrive against these statistics? During a recent iJobs event about women in academic biology, a panel comprised of accomplished female professors at Rutgers University had a few tips for rising women in academia. These tips are not limited to academia alone and can also be applied to industry positions: - Good time management skills are necessary for juggling career and family life. - Volunteering and networking can provide great opportunities for career development. - Avoid changing your personality to adapt to male-dominated environments. Instead, the key is having more confidence to show your unique skills and thus prove your self-worth. They acknowledged that unconscious bias definitely exists, but they all found a way to surpass obstacles and run successful labs. Overall, there is plenty of hope. In fact, Nature itself is making important progress by recently announcing the first woman editor-in-chief, Dr. Magdalena Skipper, in its 149 years of history13. Progress is being made, albeit slowly. Recent studies show that the gender gap in science is closing in most fields, but it will take many years to reach equity14. Some schools are taking steps towards increasing their female faculty members, with government funds backing these initiatives15. Most importantly, awareness of the issue seems to be at an all-time high. As Emma Walmsley, the first female CEO of GlaxoSmithKline, said16: “We should be much more proactive about sponsoring and supporting all types of diversity to get to the senior leadership positions”. Hopefully, this spirit is slowly prevailing in science. References: 1 Nature 558, 344 (2018). 2 UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Fact Sheet No. 43, 2017 (http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs43-women-in-science-2017-en.pdf). 3 Shen, Y.A., Webster, J.M., Shoda, Y., and Fine, I., Persistent Underrepresentation of Women's Science in High Profile Journals bioRxiv 275362; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/275362. 4 News Release, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, April 26, 2018 (https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/hsgec.pdf). 5 Survey of Earned Doctorates, National Science Foundation, June 2017 (https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2017/nsf17306/static/report/nsf17306.pdf). 6 Li, D. & Koedel, C., Representation and Salary Gaps by Race-Ethnicity and Gender at Selective Public Universities, Educational Researcher Vol 46, Issue 7, pp. 343 – 354 7 National Center for Education Statistics (https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=61). 8 TIAA Institute, Taking the measure of faculty diversity, Research Overview, October 2016 (https://www.tiaainstitute.org/sites/default/files/presentations/2017-02/faculty_diversity_overview_0.pdf). 9 ”Fortune's Most Powerful Women list stresses gender gap in pharma”, by Jacob Bell (https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/fortunes-most-powerful-women-list-stresses-gender-gap-in-pharma/505463/). 10 ”Examining faculty diversity at America’s top public universities”, by Cory Koedel (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/10/05/examining-faculty-diversity-at-americas-top-public-universities/). 11 ”The Baby Penalty”, by Mary Ann Mason (https://www.chronicle.com/article/The-Baby-Penalty/140813). 12 ”Children hurt women’s earnings, but not men’s (even in Scandinavia)”, by Claire Cain Miller (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/05/upshot/even-in-family-friendly-scandinavia-mothers-are-paid-less.html). 13 ”Nature announces new editor-in-chief”, by Holly Else (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05060-w). 14 ”New study says the gender gap in science could take generations to fix”, by Luke Holman (http://theconversation.com/new-study-says-the-gender-gap-in-science-could-take-generations-to-fix-95150). 15 ADVANCE: Increasing the Participation and Advancement of Women in Academic Science and Engineering Careers, National Science Foundation (https://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=5383). 16 “The first female big pharma CEO had the perfect response to a question about women in leadership”, by Lydia Ramsey (http://www.businessinsider.com/gsk-ceo-emma-walmsley-on-diversity-in-pharma-2018-1). This article was edited by Maryam Alapa

iJOBS Blog