Written by Abla Tannous

Every year, the Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine (CABM) at Rutgers University organizes a retreat where one person from each lab gets the opportunity to give a brief talk about their work. As I enjoy public speaking, I volunteered to give the talk this year. I have given many presentations over the years and thought this would be easy. Yet, this year was more challenging because I was about to give a presentation comparing technical approaches in mass spectrometry which can be difficult to do in 10 minutes and still engage the audience. I put the presentation together, including my own detailed images in illustrator, but I felt there was still more that I needed to do to improve my pitch. I decided to attend a workshop delivered by Dr. Dennis Mangan and hosted by the office of postdoctoral affairs on campus (https://postdocs.rutgers.edu/). Dr. Dennis is the president of Chalk Talk Science (https://www.chalktalkscience.org/) and his talk was entitled “Turning science into stories: memorable messages that make you stand out”. He started by emphasizing that scientists are problem solvers and are very effective at providing solutions. Hence, if you are a scientist stressed about giving a talk or a presentation, the solution is in your hands. You can turn your talk into a story, relax and practice.

Scientists are proficient at performing research in the lab but many times fail to effectively communicate their work to others. A big part of science is telling people about who you are, what you do in the lab and most importantly why you do it. However, a disconnect between scientists and the public occurs often when the public cannot understand, hear or remember what scientists say. Thus, scientists must turn their work into effective stories that are accessible, fun and easy to understand.

[caption id="attachment_2886" align="alignleft" width="224"] Image source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/speaker-podium-presentation-seminar-312596/[/caption]

Image source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/speaker-podium-presentation-seminar-312596/[/caption]

It might help to first define what a story is. In every story there is a problem and a goal. Actions have to be taken in order to solve the problem and reach the goal. Here is an example of how a story may be told: Beginning (setting the stage) … but one day (problem)…because of that (taking action) …until finally (solution)…and now (morale). Once scientists apply this structure while telling the public about their work, they automatically break barriers and make their science more accessible and understandable. This does not only apply while talking to the public but also when scientists communicate to each other.

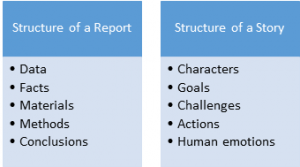

The public wants to hear about discoveries and the whole scientific journey. How hard was the work? What were their fears, failures, frustrations and firsts? When scientists incorporate all that, they give a personal touch to their stories which allows their audience to relate to what they are talking about. Here, Dr. Dennis compares the difference between a story and a report. Oftentimes, because scientists are data driven, they tend to give their presentations in the form of a report rather than a story. A report focuses on data, facts, methods and conclusions while a story has characters, goals, challenges, actions and human emotions. First, characters have to be defined to turn science work into stories. Characters may be anything or anyone. For example, a character can be the speaker, their model system, someone else they are working with, etc. It is the speaker who defines the players in the story. Using metaphors and analogies has a positive impact. For example: “the C.elegans glowed like ....” The same applies for employing senses such as smell, look or sound “As I was doing the experiment, it smelled like …” Adding emotions brings the speaker closer to their audience. Such emotions can be happiness or sadness about certain outcomes, or even horror or disgust by how something looked “I was thrilled to see that ….”

[caption id="attachment_2887" align="alignright" width="300"] Structure of a report vs. a story (Adapted from the slides of Dr. Mangan)[/caption]

Structure of a report vs. a story (Adapted from the slides of Dr. Mangan)[/caption]

Furthermore, building mystery in the story makes it more captivating and that can be done by taking pauses or using a delayed punchline approach by saying for example: “I tested this, but before I tell you the result, let me tell you about …” In addition, including questions spices up the story and creates more interest “I wonder what would happen if I tried this…”

A major factor that determines the successful delivery of a story is body language such as use of gestures, different voice tunes to beat monotony, and eye contact by facing the audience and specifically looking at individuals in the eye as if having a direct conversation. Also, being on time is of utmost importance. For a ten minutes presentation, plan for eight. Finally, it is crucial to practice the story in order to deliver a fluid message so rehearse, rehearse, and rehearse.

If you are still not convinced of the importance of telling your work in a story form, the workshop concludes that having this skill can help in various places and aspects of life, not just in science. It might help in building relationships, getting hired or even moving ahead in your career. It also can bring a lot of satisfaction. After all, this is what leaders do in order to deliver an effective message; they tell stories.

Edited by Deepshika Mishra and Thomas Kasza