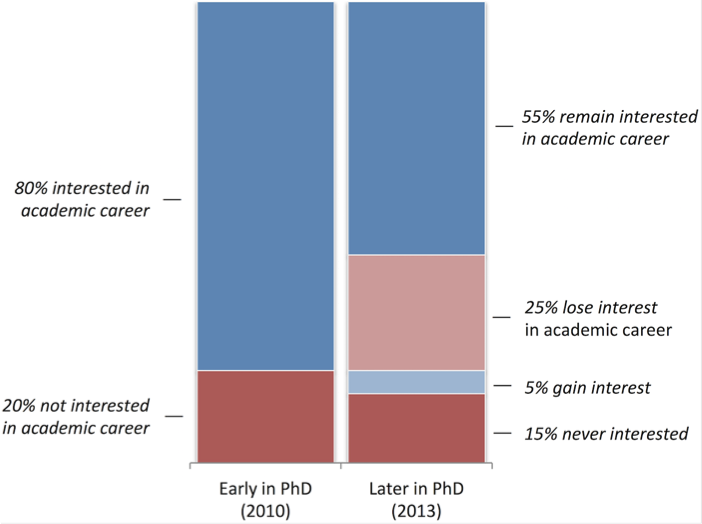

In September 2017, Michael Roach and Henry Sauermann examined the declining interest in academic careers; published in PLOS ONE . One might assume that this decline is due to a difficult job market, however, the authors found that the majority of graduate students who lost interest in academia had other reasons. The question was examined using a longitudinal survey that followed 854 Ph.D. students, in the natural sciences and engineering, from 39 U.S. research universities. The study examined students who had recently begun their Ph.D. program and then followed them to determine if their interest in academic careers had changed three years later. The specific question that was asked is “Putting job availability aside, how attractive or unattractive do you personally find each of the following careers?” Options were a range of research and non-research careers inside and outside academia.  (Roach & Sauerman, 2017) There were two main results. First, the study found that majority of students (80%) had an interest in academia when they started their Ph.D. studies, however, that number falls to 55% within 3 years. Surprisingly, approximately 25% of students lose all interest in academia. Of all students, 15% were never interested in an academic career while only 5% gained interest in an academic career. Thus, the authors pointed out that the declining interest is not a general phenomenon and is not influenced by the job market. Roach and Sauermann associated the decline to the misalignment between students’ evolving preferences for specific job attributes, and students’ changing perception of their own research abilities. I found this very surprising; prior to reading this article I would have attributed the decline in academic career interest solely to the difficult job market. Interestingly, early in their programs, students expected that about 50% of graduates in their fields would obtain an academic position but this perception significantly decreased over time. Students were also asked questions such as “When thinking about the future, how interesting would you find the following kinds of work?” The choices were: basic research, applied research, or commercialization. As expected, students who lost an interest in academic careers had a significantly decreased preference for basic and applied research and increased preference for commercialization. The survey also asked students to rate their research ability relative to their peers; students who remained interested in a faculty career had higher levels of self-reported ability. The authors also state that many of the students reported a lack of information about non-academic career options. Roach and Sauermann believe that internships may be more effective than simple workshops or information sessions. They also praised programs such as the National Institutes’ of Health’s BEST program, which promotes programs that broaden Ph.D. training. [If you’re reading this from Rutgers University, you’re in luck! It is one of the 17 institutions in the country that was awarded a BEST (Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training) grant from the NIH Common Fund. Read about BEST programs here:] The idea that all Ph.D. students are interested in academic careers is no longer accurate. Surprisingly, even among the Ph.D. students interested in academic careers, more than half of them also had an interest in industry careers. Dr. Nathan L. Vanderford, a professor at the University of Kentucky, states, “the job market doesn’t inform students’ career decisions as much as a growing understanding of what an academic career entails.” Overall, the study suggests providing more information and training for PhD candidates about the job opportunities both in and outside of academia. This will allow trainees to make more informed decisions as they prepare for their careers. There are many varied career options for scientists, and while an academic career is a great option, there are many other choices for students to consider. This study can provide useful information for those who might feel pressured into an academic career, or might not know about other options. Along with scientific training, it is important to educate yourself on the available opportunities after graduate school. If you go to an institution with the NIH BEST program, take advantage of it! If you don’t have a BEST program at your school talk to someone at the career office, which is focused on helping graduates find job placements and opportunities. Don’t be afraid to network with those around you to learn about more possibilities! Edited by Tomas Kasza and Maryam Alapa.

(Roach & Sauerman, 2017) There were two main results. First, the study found that majority of students (80%) had an interest in academia when they started their Ph.D. studies, however, that number falls to 55% within 3 years. Surprisingly, approximately 25% of students lose all interest in academia. Of all students, 15% were never interested in an academic career while only 5% gained interest in an academic career. Thus, the authors pointed out that the declining interest is not a general phenomenon and is not influenced by the job market. Roach and Sauermann associated the decline to the misalignment between students’ evolving preferences for specific job attributes, and students’ changing perception of their own research abilities. I found this very surprising; prior to reading this article I would have attributed the decline in academic career interest solely to the difficult job market. Interestingly, early in their programs, students expected that about 50% of graduates in their fields would obtain an academic position but this perception significantly decreased over time. Students were also asked questions such as “When thinking about the future, how interesting would you find the following kinds of work?” The choices were: basic research, applied research, or commercialization. As expected, students who lost an interest in academic careers had a significantly decreased preference for basic and applied research and increased preference for commercialization. The survey also asked students to rate their research ability relative to their peers; students who remained interested in a faculty career had higher levels of self-reported ability. The authors also state that many of the students reported a lack of information about non-academic career options. Roach and Sauermann believe that internships may be more effective than simple workshops or information sessions. They also praised programs such as the National Institutes’ of Health’s BEST program, which promotes programs that broaden Ph.D. training. [If you’re reading this from Rutgers University, you’re in luck! It is one of the 17 institutions in the country that was awarded a BEST (Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training) grant from the NIH Common Fund. Read about BEST programs here:] The idea that all Ph.D. students are interested in academic careers is no longer accurate. Surprisingly, even among the Ph.D. students interested in academic careers, more than half of them also had an interest in industry careers. Dr. Nathan L. Vanderford, a professor at the University of Kentucky, states, “the job market doesn’t inform students’ career decisions as much as a growing understanding of what an academic career entails.” Overall, the study suggests providing more information and training for PhD candidates about the job opportunities both in and outside of academia. This will allow trainees to make more informed decisions as they prepare for their careers. There are many varied career options for scientists, and while an academic career is a great option, there are many other choices for students to consider. This study can provide useful information for those who might feel pressured into an academic career, or might not know about other options. Along with scientific training, it is important to educate yourself on the available opportunities after graduate school. If you go to an institution with the NIH BEST program, take advantage of it! If you don’t have a BEST program at your school talk to someone at the career office, which is focused on helping graduates find job placements and opportunities. Don’t be afraid to network with those around you to learn about more possibilities! Edited by Tomas Kasza and Maryam Alapa.

iJOBS Blog