By Rebecca Manubag

On April 5, 2021, Rutgers iJOBS and the The Erdos Institute hosted an informative seminar with featured guest, Dr. Karen Akinsanya, who discussed her work in industry. Dr. Akinsanya spoke about her journey from her graduate studies to multiple positions that expanded her “breadth and depth” (as she put it) during her transition to translational science in industry. She also touched on the importance of collaboration in the field of drug discovery and gave some career tips for young scientists interested in this field.

Dr. Karen Akinsanya hails from the U.K., where she completed her doctoral and post-doctoral work, the latter exposing her to the pharmaceutical industry at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research. She joined Ferring Pharmaceuticals following her postdoc, and discussed her experience collecting clinical samples to use in the lab. This highlights a very literal example of “bench to bedside,” a term often synonymous with translational science. Over the next few years, Dr. Akinsanya continued her work at Ferring as a Senior Scientist working closely with the clinic, and even suggested the incorporation of human genetics experiments to the head of R&D at Ferring (likely influenced by the success of the Human Genome Project). An overarching question in her career seemed to be What tools are needed within drug discovery to better impact the clinic? With this in mind, Dr. Akinsanya made a 180-pivot into the world of clinical pharmacology, which eventually led her to join Merck for over a decade. She moved across many divisions during her time there, starting in the clinical department and eventually making her way to business development and licensing, proving that silo barriers can be broken with a PhD.

But what is it exactly that allowed Dr. Akinsanya to move across all of these areas so confidently? Aside from her innate determination, she was driven simply by the question of what makes a good molecule? Time and time again, she and many other researchers in her field have seen the identification of compounds that look promising in preclinical studies only to fail in the clinic.

To that end, Dr. Akinsanya next elaborated on a few reasons why drugs fail. The top reasons mentioned were molecular target validation and relevance to human disease. Even after decades of medical and laboratory innovations, one must humbly acknowledge that we still don’t know everything about the human body. This may lead to money being spent on a potential drug lead that may not even be relevant to begin with. Additionally, the current drug discovery pipeline involves roughly 5,000-10,000 compounds and up to two decades to develop a single drug from scratch. With these obstacles looming in the background, collaboration has emerged as a cornerstone of the field of drug discovery and development. An example of this is when a group is characterizing a new “hit” compound in the lab, only to find that another lab across the globe had the same idea! It’s these instances where collaboration can lead to a breakthrough, which Dr. Akinsanya speaks about in her experience working with DPPIV-related proteins.

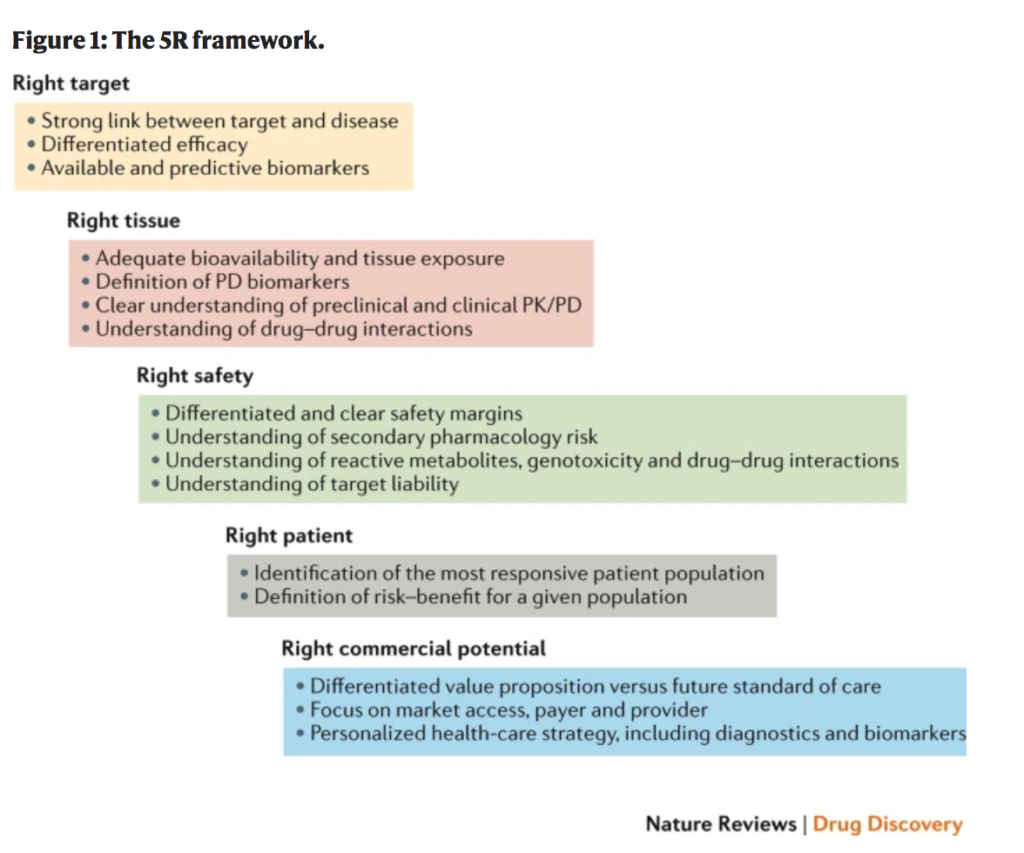

So, what makes a drug successful? The “5R Framework” from AstraZeneca was referenced to outline the general requirements for a successful drug. A drug has to have: 1. the Right target, 2. the Right tissue, 3. the Right safety, 4. the Right patient, and 5. the Right commercial potential. Unfortunately, the majority of drugs do not fulfill all of these criteria and finding a balance has proven to be quite the feat. This further emphasizes the importance of collaboration in pharma and drug discovery, since it involves risk, value, and investment. You need early clinical trials, money for funding, and maybe most importantly, partnering to incorporate ideas from many groups.

The "5R" Framework, AstraZeneca

Image reference: Morgan, P., Brown, D., Lennard, S. et al. Impact of a five-dimensional framework on R&D productivity at AstraZeneca. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 167–181 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2017.244

Dr. Akinsanya next expounded on her current work in drug discovery and translational science. For Dr. Akinsanya, her career in drug discovery has profoundly involved genomics and more recently, computational techniques. Her current work at Schrödinger focuses on the use of a computation-based approach to accelerate drug discovery. She emphasized the use of physics-based computational assays that help to model the free energy of protein binding, which can help speed up identification of useful compounds.

The use of computation and “-Omics” mapping may also be the tool needed to improve medical research. Between 2018 and 2020, the biotech industry has exceeded the number of FDA approvals for big pharma, with this generated data playing a huge part. We’ve had the first siRNA drug approved, advances in gene therapy, and the Covid-19 vaccine developed in less than a year (thanks to collaboration). Computational models can also produce real-time data from the patient population, a method that can help scale up disease-relevant information. Concluding her talk, Dr. Akinsanya also mentioned what she believed to be a promising new field of -omics in drug identification and compound screening. She referred to this as the “Pocketome,” which focuses on atomic level structures.

Dr. Akisanya’s story comes with many takeaways and she offered multiple tips for early career scientists looking to switch to industry or pharma. The first is to be proactive more than reactive. If you believe in something, make it known to your higher-ups! The second is to take calculated risks and consider the input of those with the experience you wish to seek. She also stressed the importance of finding supportive mentors in every career phase. The third tip is to identify scientific problems, but also to propose thoughtful solutions. The fourth tip is to avoid the silo effect (which can be demonstrated through her own career changes), meaning balance the breadth and depth in your career to become more interdisciplinary. Specifically, for drug discovery, this proves to be vital for the means of collaboration. Finally, she stressed the ability to respond to change in a field that is everchanging. As for making the jump from academia to industry, it may be helpful to start by seeking out smaller biotech companies to experience an industry environment.

Overall, Dr. Akinsanya managed to address multiple topics that apply to understanding her field, as well as to navigating challenges in a scientific career, in general. She used personal experiences to stress the importance of mentorship (noting multiple mentors she gained throughout her career), thinking outside the box (and making your thoughts known, like she did at Ferring), as well as keeping the common goal at the forefront of scientific decisions (in the case of drug discovery, how can more drugs be developed?). These are all takeaways that can apply to all stages of a scientific career.

This article was edited by Junior Editor, Zachary Fritz and Senior Editor, Brianna Alexander.