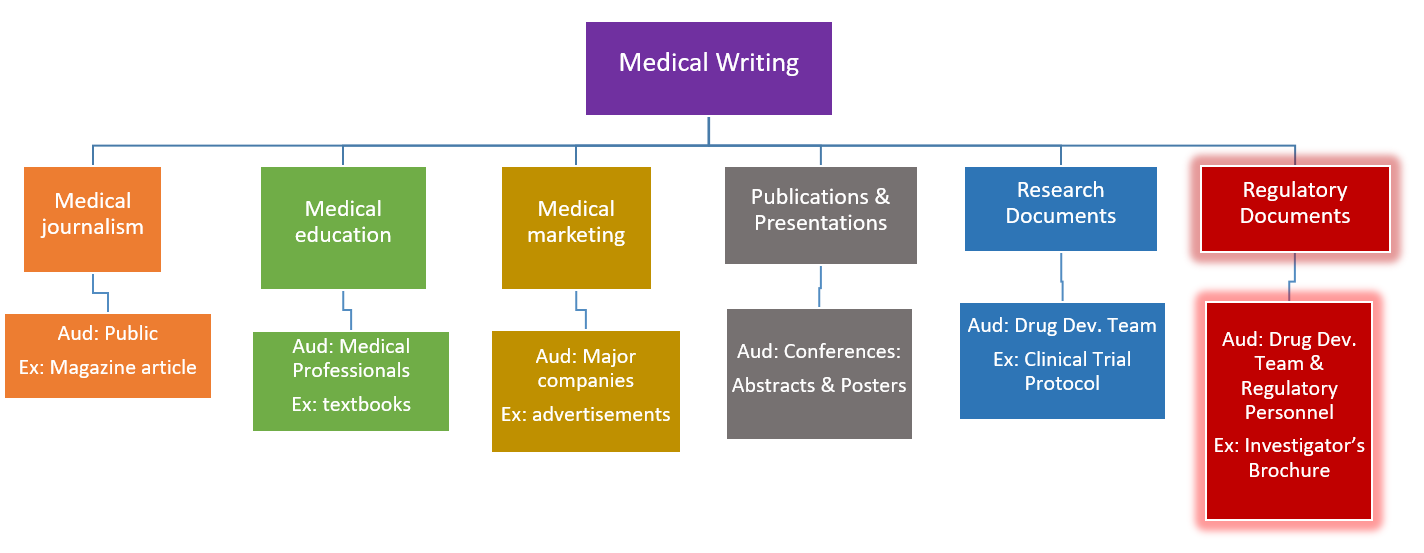

By: Brianna Alexander “The most fulfilling part of being a medical writer is being part of the treatment paradigm and knowing that what you do translates to patients and quality of life.” These are the words of Dr. Aaron B. Bernstein, a consultant medical writer, when asked to reflect on the most fulfilling part of his job as a medical writer. This past Wednesday, December 4th, Rutgers iJOBS hosted a panel/information session on careers in regulatory writing with guest speakers Dr. Aaron B. Bernstein, Marjorie Winters and Dr. Qing Zhou. Regulatory writing falls under the larger class of writing known as medical writing. Medical writing is a style of medical communication which, according to the American Medical Writer’s Association (AMWA), supports the “production of materials that deal specifically with medicine or healthcare.” Moreover, there are different fields of medical writing, each intended to provide useful health/medical-related information to a specialized audience. The chart below is a brief overview of a few medical writing subtypes. In this article we will explore the “Regulatory Documents” panel highlighted on the far right in red.  *Aud=Audience. The items listed in this chart were compiled (using Microsoft PowerPoint) based on information provided from: James Lind Institute, “Types of Medical Writing: Documents written by Medical Writers”. Posted July, 6, 2012.* So what is Regulatory Writing? Regulatory writing, according to ScienceMag, is a field in which the writer, “assists in the production of clinical documentation required by […] national regulatory agencies when assessing the safety and of drugs.” These are oftentimes documents that include Food and Drug Administration (FDA) forms, Institutional Review Board (IRB) forms and importantly, Investigator’s Brochures (IBs). Moreover, these documents are often constructed in a team effort, and help with the progression of a new drug through preclinical and clinical trials, and eventually to market. In his talk, Dr. Bernstein expanded on Investigator’s Brochures: what they are, why they are important and how they are constructed—all of which is detailed below. What is an Investigator’s Brochure and why is it important? Dr. Bernstein opened with a simple and precise definition of an IB. As sourced from: ICH E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, Section 7, Investigator’s Brochure, “An Investigator’s Brochure is a compilation of the clinical and nonclinical data on the investigational product(s) that are relevant to the study of the investigational product(s) in human subjects.” In other words, it is a document that compiles all data collected from animal and human subjects on the new drug being investigated. This type of document, Dr. Bernstein stated, can easily be 100-150+ pages and will oftentimes undergo several revisions before final submission to 1) the FDA, 2) the IRB and 3) the investigator (usually the physician consulted to help conduct the study). He also stated that the Medical Writer in this capacity is crucial for not only writing and constructing the document, but in determining the planning and organization strategy so that the document is written and submitted on time with all relevant information. The purpose of the IB, also sourced from ICH E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, Section 7, Investigator’s Brochure, is “…to provide the investigators and others involved in the trial with the information to facilitate their understanding of the rationale for, and their compliance with, many key features of a clinical study protocol.” Some key information that these documents include are: dosing regimen, safety and usage as well as reporting of any adverse events. Thus, this information is critical for new investigators who may be interested in the use of a drug because it can help ensure that the drug is used safely and appropriately. What’s in an IB? There are various parts of an IB, as Dr. Bernstein explained, each serving a distinct purpose which supports the overall document. The first few parts of the document are the introduction and summary, which touch on the need for the drug, as well as the rationale and plan for its use. The next section is dedicated to the physical, chemical and pharmaceutical descriptions of the drug and is followed by the nonclinical data and a summary of drug toxicity. This is proceeded by data on the effect of the drug in humans as well as safety and efficacy recommendations. Lastly there are sections on marketing experience, and an overall summary of drug guidelines for the investigator. Each of these sections are presented in both a logical and chronological order that will allow the investigator to appreciate the progress of the drug and make an informed decision on what steps to take next to get the drug to patients. Practical Exercises One feature of the information-packed session was an interactive portion conducted by Marjorie Winters, a freelance medical writer and editor, aimed at reviewing the concepts that Dr. Bernstein discussed. Her presentation included true/false questions and multiple choice questions that students answered as a group; all answers were discussed to clarify points of confusion or misconception. Marjorie’s segment also included a portion called, “What to Look for in Source Material” where students had the opportunity to read a sample clinical abstract and practice extracting pertinent information (that an investigator might find important) which might be included in an IB. During this section students worked in small groups to answer the questions provided and then each answer was discussed with the entire group. This was a very nice addition to the segment which helped reinforce key points while also encouraging team building and critical thinking among students. AMWA The last portion of the event was an open segment where students got to ask questions of the AMWA members present, including Dr. Qing Zhou, president of the New York AMWA chapter, who traveled in for the event. Dr. Zhou discussed AMWA’s goals and mission—to educate and promote excellence—and shared information about how students could get on the AMWA mailing list to learn more about current and future opportunities. When asked to reflect on the most fulfilling part of being a medical writer, Dr. Zhou replied that for her it is the “intellectual contribution,” and expressed her excitement and passion in finding a career so suiting. This was overall a very informative session covering the ins and outs of medical regulatory writing as well as AMWA and how students can get involved and learn more. One of the things that I appreciated as a participant at this event was the way that the speakers all explained the relevancy of graduate training to their success in their current positions. For example, Dr. Bernstein mentioned that discipline, knowledge of the scientific method and a keen sense of organization were all skills from his graduate training that continue to be relevant in his work. In addition, I liked the inclusion of the interactive exercises in which students could engage with the material and interact with one another. This event highlighted one of the many non-traditional post-graduate careers in which writing is both essential and impactful. Junior editor: Vicky Kanta Senior Editor: Monal Mehta

*Aud=Audience. The items listed in this chart were compiled (using Microsoft PowerPoint) based on information provided from: James Lind Institute, “Types of Medical Writing: Documents written by Medical Writers”. Posted July, 6, 2012.* So what is Regulatory Writing? Regulatory writing, according to ScienceMag, is a field in which the writer, “assists in the production of clinical documentation required by […] national regulatory agencies when assessing the safety and of drugs.” These are oftentimes documents that include Food and Drug Administration (FDA) forms, Institutional Review Board (IRB) forms and importantly, Investigator’s Brochures (IBs). Moreover, these documents are often constructed in a team effort, and help with the progression of a new drug through preclinical and clinical trials, and eventually to market. In his talk, Dr. Bernstein expanded on Investigator’s Brochures: what they are, why they are important and how they are constructed—all of which is detailed below. What is an Investigator’s Brochure and why is it important? Dr. Bernstein opened with a simple and precise definition of an IB. As sourced from: ICH E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, Section 7, Investigator’s Brochure, “An Investigator’s Brochure is a compilation of the clinical and nonclinical data on the investigational product(s) that are relevant to the study of the investigational product(s) in human subjects.” In other words, it is a document that compiles all data collected from animal and human subjects on the new drug being investigated. This type of document, Dr. Bernstein stated, can easily be 100-150+ pages and will oftentimes undergo several revisions before final submission to 1) the FDA, 2) the IRB and 3) the investigator (usually the physician consulted to help conduct the study). He also stated that the Medical Writer in this capacity is crucial for not only writing and constructing the document, but in determining the planning and organization strategy so that the document is written and submitted on time with all relevant information. The purpose of the IB, also sourced from ICH E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, Section 7, Investigator’s Brochure, is “…to provide the investigators and others involved in the trial with the information to facilitate their understanding of the rationale for, and their compliance with, many key features of a clinical study protocol.” Some key information that these documents include are: dosing regimen, safety and usage as well as reporting of any adverse events. Thus, this information is critical for new investigators who may be interested in the use of a drug because it can help ensure that the drug is used safely and appropriately. What’s in an IB? There are various parts of an IB, as Dr. Bernstein explained, each serving a distinct purpose which supports the overall document. The first few parts of the document are the introduction and summary, which touch on the need for the drug, as well as the rationale and plan for its use. The next section is dedicated to the physical, chemical and pharmaceutical descriptions of the drug and is followed by the nonclinical data and a summary of drug toxicity. This is proceeded by data on the effect of the drug in humans as well as safety and efficacy recommendations. Lastly there are sections on marketing experience, and an overall summary of drug guidelines for the investigator. Each of these sections are presented in both a logical and chronological order that will allow the investigator to appreciate the progress of the drug and make an informed decision on what steps to take next to get the drug to patients. Practical Exercises One feature of the information-packed session was an interactive portion conducted by Marjorie Winters, a freelance medical writer and editor, aimed at reviewing the concepts that Dr. Bernstein discussed. Her presentation included true/false questions and multiple choice questions that students answered as a group; all answers were discussed to clarify points of confusion or misconception. Marjorie’s segment also included a portion called, “What to Look for in Source Material” where students had the opportunity to read a sample clinical abstract and practice extracting pertinent information (that an investigator might find important) which might be included in an IB. During this section students worked in small groups to answer the questions provided and then each answer was discussed with the entire group. This was a very nice addition to the segment which helped reinforce key points while also encouraging team building and critical thinking among students. AMWA The last portion of the event was an open segment where students got to ask questions of the AMWA members present, including Dr. Qing Zhou, president of the New York AMWA chapter, who traveled in for the event. Dr. Zhou discussed AMWA’s goals and mission—to educate and promote excellence—and shared information about how students could get on the AMWA mailing list to learn more about current and future opportunities. When asked to reflect on the most fulfilling part of being a medical writer, Dr. Zhou replied that for her it is the “intellectual contribution,” and expressed her excitement and passion in finding a career so suiting. This was overall a very informative session covering the ins and outs of medical regulatory writing as well as AMWA and how students can get involved and learn more. One of the things that I appreciated as a participant at this event was the way that the speakers all explained the relevancy of graduate training to their success in their current positions. For example, Dr. Bernstein mentioned that discipline, knowledge of the scientific method and a keen sense of organization were all skills from his graduate training that continue to be relevant in his work. In addition, I liked the inclusion of the interactive exercises in which students could engage with the material and interact with one another. This event highlighted one of the many non-traditional post-graduate careers in which writing is both essential and impactful. Junior editor: Vicky Kanta Senior Editor: Monal Mehta

iJOBS Blog