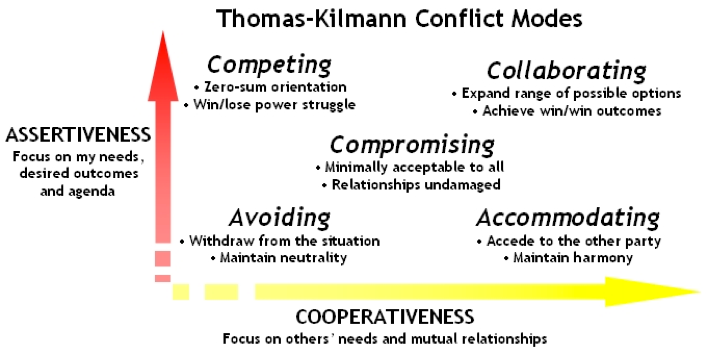

By Jennifer Casiano-Matos On February 21st, I had the opportunity to participate in a talk about managing conflict and feedback by Dr. Lori Conlan from the Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) at NIH. This talk was part of a training series on developing the tools for a successful training or career experience, and more specifically, improving workplace dynamics. In her talk, we discussed several aspects on how to identify a conflict, solve it and most importantly give and manage feedback to other colleagues. Every day of our lives there is potential for conflict and as scientists, we are not exempt. For example, there can be conflicts in publishing your research when you want to publish small pieces in low impact journals, but your PI wants all or most of your research published in a more high impact journal. There is conflict in roles (who is supposed to do what), clashing personalities, authorship, work styles, and schedules. There is conflict in the scientific methods we try to use, the values of work-life balance, priorities, quality of the data, timing, and resources. As we can see, there is potential for conflict everywhere. This is supported by the results of an interesting workshop for scientists conducted by Cohen and Cohen; they found that 75% of the scientists report spending 10-15% of their time on “people problems,” more than two thirds reported “uncomfortable interactions with 1-5 people weekly, and that interpersonal conflict hampered the progress of a scientific project between 1-5 times during their careers. After reading this, you might be asking yourself why this is still happening? The reality is that some of the previous generations of scientists did not have the resources to manage conflict and learn the appropriate methods for constructive feedback. Currently, there are many programs and resources at colleges for graduate students and postdocs to learn how to manage the daily problems that we all can encounter in a work setting. However, we need to understand that some conflict has its benefits. For example, a healthy argument can boost creativity and the flow of new ideas. Having conflict in our work environment put on practice communication, emotional control, energize and group by verbalizing needs. You can improve the ability to listen, be more flexible and negotiate. However, how does one manage conflict in an effective way? The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Grid shows seven different methods that we can manage conflict. Assertiveness is defined as how important it is to get your task done and cooperativeness is how important the relationship is between the individuals involved. For example, the higher the assertiveness the more important it will be to get your task done. In addition, if the relationship between the individuals is not important then the conflict will turn into a competitive one; however, if the relationship is important, a collaboration will evolve which will result in a win-win situation. When you are in competing mode you do not care about the relationship which leads to a win or lose power struggle. In contrast, people that tend to avoid the conflict get sucked in to protect themselves. It can be a safety measure or a way to get one’s needs met. Accommodating is a behavioral attempt to satisfy the other person’s needs to maintain a good relationship and harmony and one that many graduate students and post-docs gravitate towards. To achieve a compromise behavior can be difficult but it is mainly finding a balance. Give a little and take a little. Finally, collaborating is what builds relationships and is defined by a win-win relationship.  No matter how you decide to approach the conflict, it is important to manage the feedback from the other person. You will need to, for example, describe the situation which will put the feedback into context, time, place or circumstance; the behavior which is the observable action, and the impact that the conflict has on you; in other words, how you feel. In general, you want to discuss the conflict by describing what you observed; you could confidentially meet with the person and tell them what is happening and why it is a conflict. Share the impact the conflict has on you, how you felt, and how it affected you. You want to give the individual the chance to respond- to tell you if there is anything they agree or disagree with. Offer suggestions on how to solve the problem and express support. After addressing the conflict, you might encounter different responses and you should be prepared for them. Common answers could range from:

No matter how you decide to approach the conflict, it is important to manage the feedback from the other person. You will need to, for example, describe the situation which will put the feedback into context, time, place or circumstance; the behavior which is the observable action, and the impact that the conflict has on you; in other words, how you feel. In general, you want to discuss the conflict by describing what you observed; you could confidentially meet with the person and tell them what is happening and why it is a conflict. Share the impact the conflict has on you, how you felt, and how it affected you. You want to give the individual the chance to respond- to tell you if there is anything they agree or disagree with. Offer suggestions on how to solve the problem and express support. After addressing the conflict, you might encounter different responses and you should be prepared for them. Common answers could range from:

- Avoidance: be assertive and tell them that you want to hear their side.

- Excess emotion: tears, anger, sarcasm – just take a break and talk later.

- Denial: “no I didn’t” …

- Generalization: “everyone else does the same thing”- tell the person to focus on themselves and the problem.

- Withdrawal: not engaging the discussion- tell the person that you really want to hear their side.

- Over personalization: making the performance about you…” Why don’t you support me/ value me”? - try to tell them to focus on themselves.

- Focus on rules: you said X I did X

- Attacking: yelling- take a break.

- Explaining without owning: giving personal reasons, talking about stress and deadlines – talk to the person and discuss strategies on how to get things done and ways to focus during a difficult period.

Managing conflict and feedback is always difficult but a necessary skill. You need to understand that sometimes you need a do-over and start fresh with that person in order to succeed. My advice is that you need to choose your battles, sometimes complaining about simple stuff is not necessary, especially if you will need to interact with that person in the future. However, respect yourself and value your time. If a conflict is disrupting your performance and routine it is always best to talk about it earlier than later.