I don’t have to tell you that pursuing a PhD is a huge undertaking that is extremely stressful; we have all become well aware of that. It has been my impression that the general culture in graduate schools everywhere prioritizes time in lab and subsequent deliverables including results, conference presentations, and publications. After all, we are here to be trained as scientists and gain a deep expertise in a particular field. But, I’m sure to the chagrin of many a PI, graduate students are not robots. We are people, whose health and well-being are comprised of the physical, the mental, and the emotional. Herein lies a truth that I had to learn the hard way: these aspects are not mutually exclusive and they each hold equal importance. In lieu of spinning a TL;DR autobiographical cautionary tale, I want to talk about the very real issues of stress and burnout in graduate school and provide some tips on how to recognize it, prevent it, and recover from it, based on my personal experience.

Stress is part of the package when you sign up to be an adult let alone a graduate student in a high pressure environment. In addition to our own thesis research project, we play roles of varying sizes in managing the lab, helping to write grants, mentoring undergraduates and new graduate students, teaching classes, and are often also involved in multiple side projects and collaborations. On top of this, our lives outside of school don’t pause to allow us to exclusively push the boundaries of science. Trying to deal with it all can feel like too much. That is the essence of stress: having too many things demanding your limited physical, mental, and emotional resources. Symptoms of stress include anxiety, irritability, emotional overreaction, poor concentration, and an endless list of physical problems including fatigue, sleep disturbances, body aches and pains, hair loss, and digestive troubles. In the midst of this distress, however, there is often a light at the end of the tunnel, where we will feel that things will get better once items A – Z are completed.

But what happens when you don’t see an end? I believe our culture fosters the delusion that if we just work harder, everything will fall into place. Unchecked, relentless stress leads to burnout, where those limited resources that were being drawn on by everything going on in life have been completely used up. A student who is burning out may feel like they have no control over what is happening to them and see no possibility of positive change in their situation, which comes dangerously close to feeling that life is not worth living anymore. Physically, the same effects of stress on the body may become more pronounced during burnout. Emotionally, a student experiencing burnout may feel helpless, trapped, numb, detached, unmotivated, cynical, and defeated. Feelings of failure conflict with our past pattern of being high-achieving, which was part of what got us into graduate school. The tendency of most of us to be Type A perfectionists makes the risk of burnout all the more real. These emotions can lead to behavioral changes such as disregarding responsibilities, isolation, procrastination, skipping lab altogether, taking frustrations out on others, and substance abuse.

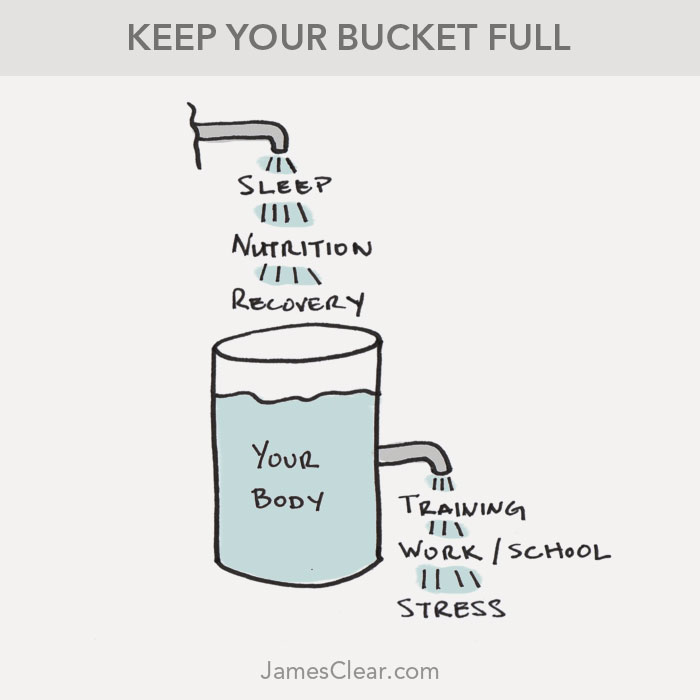

But there is hope! Thankfully, burnout, while extremely distressing, is preventable and reversible. To prevent burnout, it’s important to recognize the symptoms of stress and intervene to manage and alleviate them. As is the case for treating many maladies, it is essential to put down the ramen packets and adopt a healthy diet, engage in physical activity, and SLEEP! There are several other less obvious ways to prevent burnout:

[caption id="attachment_543" align="alignnone" width="700"] http://jamesclear.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/recovery-bucket.jpg[/caption]

http://jamesclear.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/recovery-bucket.jpg[/caption]

- Start and end your day with a relaxing activity/ritual. Before I learned this, I used to wake up and check my email on my phone before even getting out of bed, immediately putting myself in work mode. Try taking even just 15 minutes to do some yoga, journaling, reading, or mediation before you jump into the day’s tasks or turn in for the night.

- Unplug from technology daily. In today’s world, it’s harder and harder to detach from our phones, computers, emails, and social media. But try to find some time each day to power down and disconnect.

- Separation of home and lab. In my experience, in times of high stress, worries about research and personal things get blurred into one crescendo of anxiety. The best way for me to prevent this has been to leave lab at lab, meaning that I don’t bring work home. If there is something that urgently needs to get done, I will stay at school to finish it rather than work on it at home. My home and personal space belong to me, not work.

- Set boundaries and be assertive in prioritizing your well-being. Related to the previous point, it is important to set boundaries both in lab and in your personal life, restoring “yes”/“no” equilibrium. This includes saying no to some side projects or more undergraduate students. Now, I know that’s immensely easier to say than do, particularly with PI’s of varying personalities, but it can be worth it. More abstractly, set boundaries with your project, meaning that you don’t allow it to be connected so deeply with your self-worth. Science is fickle, but your worth is unwavering!

- Tell someone! As described above, some of the most damaging and dangerous signs of burnout are not visible. The person in lab with the biggest smile could be going through immense turmoil. So if you are experiencing a lot of stress and are feeling overwhelmed, it is imperative to let someone know, including your PI.

- Take breaks and time off. To prevent drainage of your resources, time off is essential to recharge. This doesn’t have to be 2 weeks of vacation, but taking evenings or a weekend to do something fun, relaxing, or creative can prevent having to take 3 months off after burnout, as was the case for me. Don’t worry; you will not add another year in grad school because you went camping last weekend.

- Utilize support systems. You may feel the desire to isolate yourself to keep people from further draining on your resources, but the opposite is what is needed. Support systems come in many different forms, including friends, family, mentors, counselors, and pets too. Your PI and committee can also be sources of support in that you can try to more frequently access them for advice on projects you may be having trouble with or finding a way to eliminate some unnecessary projects. Rutgers Counseling, ADAP, and Psychiatric Services (CAPS, 848-932-7884) provide free counseling to students and were a major part of my stress management. Other resources in times of crisis include Rutgers Acute Psychiatric Emergency Services (732-235-5700), NJ HopeLine (855-654-6735), and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-8255).

When the burnout has already happened, it’s not too late! After you’ve reached your breaking point, it’s time to employ more intense strategies. This means slowing down and maybe taking a longer period of time off. During my 3 months away from lab, I at first felt guilty for doing so. This is natural, but remaining in the same environment that caused the burnout will only make things worse while you try to recover. I was very fortunate to have a committee that cared about me as a person and recognized the importance of my taking this time to heal. Take this time to engage with a professional therapist and support systems and evaluate what got you to this place so you can recognize it and intervene in the future. This also provides the opportunity to do some soul searching, figuring out what brings you joy and what you need to be both happy and successful in science – it’s possible!