We have all been told at one point or another that the skills we develop in graduate school can be translated into industry value if we communicate them properly. However, I have always wondered about the credibility of this statement. How can technical lab skills be helpful in non-academic career tracks? My curiosity on the issue led me to a recent article featured in Science, where the author compiles expert opinions from scientists across various non-academic career tracks to showcase how they integrate skills gained from graduate school/post-doctoral training into their current positions.

[caption id="attachment_1669" align="alignright" width="352"] Click to enlarge[/caption]

Click to enlarge[/caption]

Kenneth Gibbs Jr. is the Director of the Division of Training, Workforce Development, and Diversity at the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). He explained how the natural curiosity and passion for discovery innate to scientists are just the traits a hiring manager may look for in an ideal candidate since these skills will help drive a company to the next level. For example, in graduate school not only did Gibbs read the literature on his thesis project, but he also actively questioned experts in the field to address complex issues. In his policy research position, the methodology has not changed. He actively reads and studies topics to come up with strategies, which is aided by his scientific background. Therefore, I think his advice of actively seeking help is something graduate students should pay attention to. In our training we may find ourselves bogged down with data analysis and immense workloads which eventually become obstacles to approaching problems systematically. Regular meetings with our advisor(s) and thesis advisory committee can come to the rescue and make graduate school a stimulating rather than taxing experience.

Christopher Stern who is a life sciences consultant hails the power of communication as a critical skill for scientists to develop. The process of reading literature, coming up with a hypothesis, testing it by experimentation, and presenting the results to an audience in the form of grants, papers or presentations is still applicable to his daily duties as a science communicator. Brief and effective expression of ideas can make or break a deal in the communication field as one can have a matter of minutes to convince their supervisor or client about an approach. Field application specialist Kyle Nakamura, also stresses the power of communication. He has to deal with a broad spectrum of audiences in his line of work. He stresses that having to engage various audiences during his graduate/post-doctoral training has paid off and even given him an edge at work. Joshua Hall, Director of science outreach and the Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill also reverberates this sentiment and stresses the importance of connecting science with the public.

Shelia Cherry, President and senior editor of Fresh Eyes Editing, wears multiple hats daily as she functions as the editor, supervisor, writer, teacher, and bookkeeper of her business. Most of us can relate when she talks about the seemingly universal problem of time management. She suggests making a to-do list on a daily basis and planning the day out accordingly. In my own experience, the to-do list I make for lab every weekend has proven invaluable in functioning efficiently each week as a graduate student.

Jennifer Reininga-Craven is the Associate director of research development at the Duke University School of Medicine. She opines how the skills developed in graduate school (eg. tackling complex problems by breaking them down to manageable levels) became useful in her role as a research development professional. Additionally, years of basic research training helped develop her eye for detail, which continues to aid her current grant writing efforts.

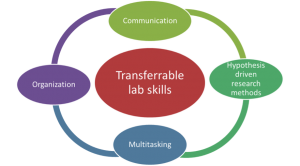

Thus, as graduate students and post-docs we should focus on honing our skills in various arenas: be it communicating our work verbally or in writing, reaching out to the public, or adopting a highly organized approach in our daily scientific endeavors. All these skills can go a long way in paving the way for an illustrious career in both academic and non-academic tracks.

The original article by Maggie Kuo, published in Science, can be found here.

Share some of the transferable skills you've picked up in graduate school below!