By Juliana Corrêa-Velloso

Graduate students and postdocs operate on both sides of leadership. As students they are mentees, but for newer and junior level lab members they serve as mentors. Although these key interactions are as important as the technical skills acquired during the PhD, they are often neglected. Looking back at your PhD training do you remember being prepared to be a leader? More importantly, do you recognize yourself as a potential inclusive leader? On February 11, iJOBS hosted the How to be an Inclusive Leader seminar led by Dr. Srikant Iyer, director of the Science Alliance program at The New York Academy of Sciences. Dr. Iyer shared his knowledge on the leadership skills for scientists and offered some directions of how to be a mindful and inclusive leader.

Most PhD students learn interpersonal skill management based predominantly on personal experiences and environment around them. I am sure many of us, at some point of our career have doubted our leadership capacity. Negative feelings toward leadership positions such as “I am the wrong person for this” or “I can’t do that” can unfortunately be common recurring thoughts. To change perspective of these thoughts, Dr. Iyer encouraged the participants to reflect on what motivated them to apply for a graduate program as his introduction to the seminar. “What were the skills that made you a good candidate to the program? And why did you select that specific program?”, Dr. Iyer pressed. Possessing traits like curiosity, enthusiasm, and strong communications skills, set PhD students on a strong leadership development pathway, he explained. And if you believe that your record with leadership experiences is not ideal, no worries. According to Dr. Iyer leadership traits can be developed and trained. But how?

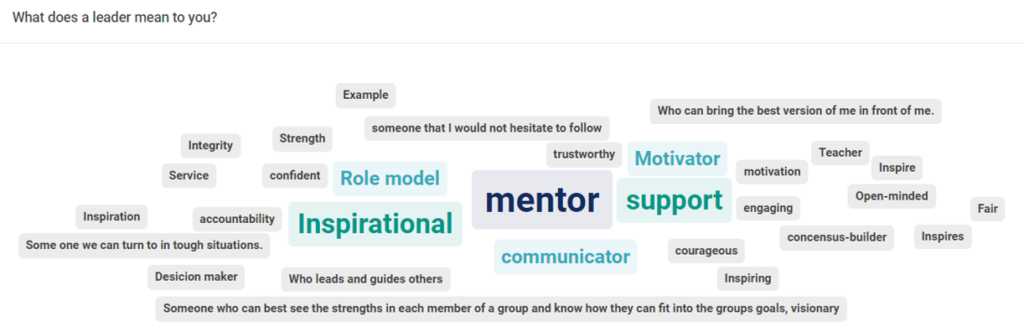

During the seminar, attendees were asked to describe what being a leader meant to them. The audience generated a word cloud that showed words describing leadership characteristics such as “mentor, inspirational, support, role model, motivator and communicator”. Indeed, these characteristics matched with the classic figure of a mentor, a crucial player in the academic formation. PIs and senior postdocs do provide some guidance to PhDs students and junior postdocs on leadership development based on their own experiences. However, this important task should not rely solely on personal experiences or common-sense knowledge about a specific matter. Without structured science-based orientation about their leadership approach, mentors can be misled by implicit bias. To build up a new generation of inclusive leaders we need to look back at how current leaders were shaped.

Figure 1: Screenshot from Dr. Iyer seminar. Attendees were asked to define what does a leader means to them. The image represents the word cloud formed by the answers.

Based on a study from American Psychologist Journal1, Dr. Iyer described the status of the leadership culture in the United States in the early nineties. This study showed that rather than being chosen based on leadership skills, first line supervisors were chosen based on job-related technical skills with a correlated 60%-75% rating of poor managerial competence. The study also highlighted the importance of the feedback from subordinates, peers, and superiors to the evaluation of the leader. Considering the importance of a leader for the functionality of an organization, the consequences of working with unfitted and untrained leaders can go beyond the dysfunctional interaction in a group to affect the whole system. Ultimately, investment in all parties involved in that alliance, at both the individual and organizational level is critical to achieve a constructive and beneficial work environment.

One of the main characteristics of a compassionate leader is equity. In terms of a group, equity means equal opportunities while equality means equal resources. Diversity comes from the inclusion of underrepresented groups. Diversity equity, therefore, is equal opportunity for these groups. It is impossible to talk about equity without thinking about inclusion. As Dr. Iyer explained, considering team gender, ethnicity, disabilities, LGBTQIQA+, and different cultural backgrounds is essential to a healthy leadership culture. He also highlighted the importance of understanding some relevant theoretical concepts to have fruitful discussion about inclusion and representation in the workplace. Dr. Iyer showed a practical example formulated by Dr. Robert Seller, Chief Diversity Officer at University of Michigan to emphasize his point. “Imagine that a dance party is being organized. In that context, diversity happens when everyone is invited to the party. Equity will happen if everyone gets to contribute to the playlist. Inclusion is allowing everyone the opportunity to dance”, he said. This good example shows that the assimilation of these key concepts is essential not only for a throwing a good party, but also for nurturing a prosperous workplace environment (please, wait for the pandemic to be over to put that example in practice!).

Awareness about others is key to inclusive leadership. A longitudinal university-wide study2 showed that STEM classes taught by “fixed mindset” faculty have larger racial achievement gaps and inspire less student motivation compared to classes taught by faculty with a “growth mindset”. According to the study, faculty mindset beliefs predicted student achievement and motivation above and beyond any other faculty characteristic, including their gender, race/ethnicity, age, teaching experience, or tenure status. In fact, implicit biases related to gender, race, and culture, are deeply rooted in society and substantial barriers faced by underrepresented groups. Another important aspect is the quality of the communication of a leader. According to a Harvard Business Review3, men are more often positively described in their performance reviews compared to their female counterparts. The impact of these canonical leadership shortcomings can affect all steps in career development. To overcome these problems, educational initiatives and implementation of inclusive policies are necessary to start and guarantee needed leadership inclusivity changes. From this perspective, it is clear that key representatives within an organization, and the organization itself, need to be responsible for identifying and creating policies in preventing these biases.

An inspirational initiative cited by Dr. Iyer, is The Open Chemistry Collaborative in Diversity Equity (OXIDE). By hosting equity workshops and conducting demographic assessments, OXIDE contributes to the reducing of inequitable policies and practices that have historically led to disproportionate representation on academic faculties with respect to gender, race-ethnicity, disabilities, and sexual orientation. As a result of this kind of initiative, additional inclusive practices are being discussed across universities. For example, the traditional “wall of fame” from most university departments are not representative and diverse, reinforcing a single type of stereotype. With the promotion of inspirational examples from all demographic groups, universities can find a balance between celebrating the past without jeopardizing the future. By encouraging personal growth and advocating for inclusive policies, best practices of leadership will evolve. Individuals need to be allowed to be themselves to achieve their full potential and bring to the table their unique contribution. As Dr. Iyer explained, by covering their personal identity to fit into a professional identity, the potential for innovation, creativity, and success is downplayed.

By encouraging personal growth and advocating for inclusive policies, best practices of leadership will evolve. Individuals need to be allowed to be themselves to achieve their full potential and bring to the table their unique contribution.

- Dr. Srikant Iyer

Now that we have an idea about how a nurturing workplace environment should be, how can you prepare yourself to be an inclusive leader? Here are some final takeaways from Dr. Iyer’s seminar:

- List your strengths and values and keep the list close to you. As a STEM PhD, you certainly already have several leadership skills.

- Remember, as any other skill, leadership skills are acquired. Be intentional about your goals and training.

- Have an open-minded approach and educate yourself about equity, diversity, and inclusion. In the process, be gentle with yourself and with others. Be mindful that each one has a diverse cultural background and different levels of literacy on these subjects. That is why engaging in educational initiatives are important.

- As a woman, if you struggle with Impostor Syndrome, remember that you are in an environment that suffers from a lack of inequity. Good materials to read are the paper Impostor Syndrome: Treat the Cause, not the Symptom by Mullangi and Jagsi4 and the study report: Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine5.

- During the seminar, Dr. Iyer and the attendees discussed 2 case-studies related to equity, diversity, and inclusion in the academic set-up. I strongly recommend readers view the recording of the event at the iJOBS events page and enjoy the constructive discussion about the cases.

I hope this article helps you to envision yourself as an inclusive leader and inspires you to nourish your colleague’s growth along the pathway.

References:

- Robert Hogan, Gordon Curphy, Joyce Hogan. “What We Know About Leadership Effectiveness and Personality”, American Psychologist, 1994.

- Elizabeth Canning, Katherine Muenks, Dorainne Green, Mary C. Murphy. “STEM faculty who believe ability is fixed have larger racial achievement gaps and inspire less student motivation in their classes”, Science Advances, 2019.

- David Smith, Judith Rosenstein, Margaret Nikolov. “The Different Words We Use to Describe Male and Female Leaders”, Harvard Business Reviews, 2018.

- Samyukta Mullangi, Reshma Jagsi. “Imposter Syndrome, Treat the Cause, Not the Symptom”. JAMA, 2019.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine; Committee on the Impacts of Sexual Harassment in Academia; Paula A. Johnson, Sheila E. Widnall, and Frazier F. Benya, Editors. “Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine”, 2018.

This article was edited by Senior Editor Samantha Avina.