By Antonia Kaz

Publishing your work in a journal is an opportunity to share a new finding or perspective with the scientific community. It is a foot in the door as a fledgling scientist or principal investigator (PI). However, the priorities of authors often differ from those of the journal editors with whom they seek to publish. The iJOBS Navigating the Publication Process event provided invaluable advice from a Rockefeller University Press editor, Dr. Andrea Marat. Dr. Marat, who was a Senior Scientific and Reviews Editor at the time of the event, has been working at the Journal of Cell Biology (JCB) since 2016 and is currently the Deputy Editor. Dr. Marat provided an in-depth overview of the editorial and peer review processes, highlighting key dos and don'ts for authors.

Before delving into the editorial process, Dr. Marat emphasized the importance of considering a fundamental question when selecting a journal: “Who is [your] main audience, and what journals do they read?” While the prestige of journals like Cell Press, Nature, or Science may be alluring, she advised, “You should always think about making your paper visible to the appropriate audience.” This blog post will guide you through the editorial and peer review processes from the perspective of a journal editor.

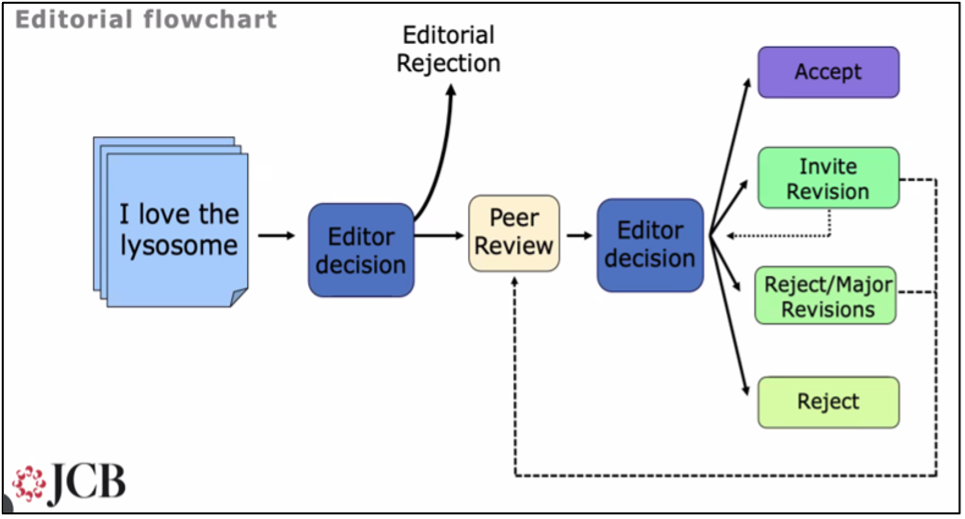

The editorial process

Journal editors typically seek publications that are relevant to their readership, addressing long-standing debates, unresolved questions, or introducing new concepts and findings in the field. As an author, it is your job to figure out the big picture of your work. Dr. Marat recommends focusing on convincing your audience that you are trying to solve an interesting problem in the field, rather than solely aiming to impress an editor with your findings.

To determine whether your publication is appropriate for a particular journal, it is crucial to understand the scope of the journals you are considering for submission. This sometimes is a better indication of the relevance of your publication than the journals publication archive, as technological advances and new findings often shift the focus of a specific field or journal. If you are still uncertain whether your findings would resonate with the journal’s readership, consider submitting a pre-submission inquiry to the editors. Pre-submission inquiries are intended to warn authors if their submissions are not suitable for JCB, they are not a prerequisite for submission.

While pre-submission inquiries may not be required for every submission to JCB, Dr. Marat strongly recommends submitting a cover letter. At JCB, a cover letter is not to declare your submission, as you might have done for a grant submission. Instead, it is an opportunity to convince editors that your work is broadly interesting to their readership and to explain why certain reviewers, referees, or editors should or should not be involved in the editorial process. Dr. Marat also advised addressing editors by their name, rather than using “Dear Editor,” and summarizing your findings in a way that highlights their novelty.

Regarding the manuscript itself, Dr. Marat’s number one tip for writing a paper is formatting. Though many journals, including JCB, are format neutral, you should include the following: page numbers, ideally as line numbers; figure numbers, title and legend with relevant details of the experimental setup; high resolution figure images; and a clear font at an appropriate size. Remember, reviewers are busy and often review submissions during their commutes. So, make sure your paper passes the airplane test: can a PDF file of your text, figures, and figure legends be easily viewed on a small screen? If not, consider reformatting to avoid frustrating a reviewer.

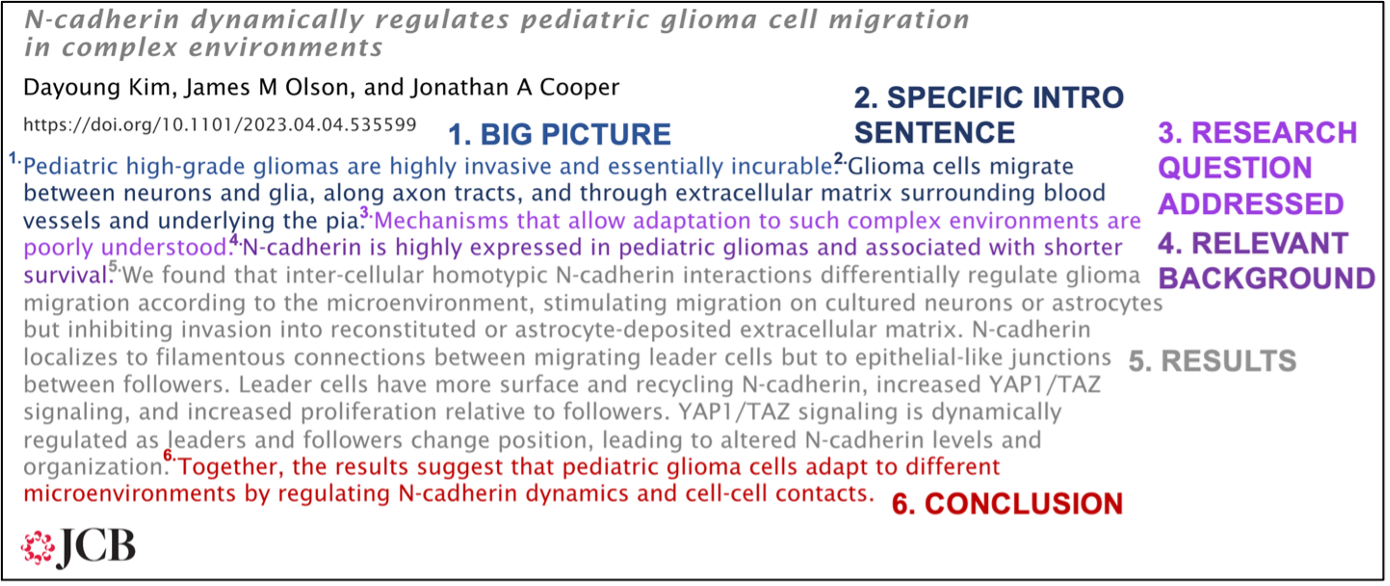

When writing your paper, Dr. Marat suggests being precise and concise. Avoid jargon and overly technical terms and reduce the number of propositions and nominalization. For instance, “formation of aggregates” can be rephrased as “aggregate formation.” Many scientists do not have time to read every paper in full, so a well-crafted abstract is crucial. Consider using this formula when writing your abstract: a big picture sentence, specific introductory sentence, sentence addressing your research question, sentence (or two) providing relevant background, results, and concluding sentence. The following was used as an exemplary abstract:

This exemplary abstract flows seamlessly through the key components. Understanding your audience and respecting their time can increase the likelihood of your publication being accepted and read by a broader audience.

The peer review process

In the second half, Dr. Marat discussed the peer review process, where a group of reviewers evaluates submissions after initial editorial approval. Many journals aim to minimize biases during peer reviews. Although pilot studies on the effectiveness of double-blind peer reviews have been conducted, the results remain inconclusive. As a review editor, Dr. Marat chooses not to look up the authors before reading their submission and sometimes remains unaware of the most prominent scientists outside her field. However, this approach is not universal to reviewers. To mitigate biases and diversify the reviewer pool, JCB records author and reviewer demographics. Additionally, JCB prioritizes reviewers who offer fair and constructive criticism. Dr. Marat does not see the value in a reviewer who criticizes a paper without providing feedback grounded in empirical evidence or established concepts.

For graduate students or post-docs interested in the peer review process, Dr. Marat recommended seeking guidance from a peer reviewer (e.g., your PI or a mentor) on how to get involved. JCB highly encourages young scientists to participate in peer review as it offers an excellent opportunity to gain experience and receive recognition as a co-reviewer.

After the peer review process, a second editorial decision is made to reject, accept, or suggest revisions. Editors decide whether to reject a submission based on the arguments presented by the peer reviewers. It is not an electoral system. Editors at JCB carefully evaluate the peer reviewers’ comments to determine if the experiments are sound, whether more data is needed, and if all aspects of the paper fall within the scope of the study. If your submission does not meet these criteria, JCB will provide detailed feedback in a rejection letter. For example, stating when an experiment needs a control to strengthen the findings. JCB also offers guidance for revisions, and Dr. Marat proudly noted that JCB has a greater than 95% acceptance rate for invited revisions. From her perspective, if authors address all revisions and there is no data contradicting the experiments, the journal has an incentive to publish the work. When resubmitting, it is important to reiterate the reviewers’ initial recommendations and comments at the beginning of your resubmission. If a revision is no longer necessary, explain why at the outset.

While it is possible to appeal a rejection, this should only be done if you believe there was a factual error, a flawed interpretation of your findings, or if you can completely address criticisms with new data. An appeal should be a clear and concise explanation why your paper should be accepted. It should provide new data or planned experiments to be incorporated into a revised manuscript. It is NOT an opportunity to attack the reviewers and editors. Maintaining good relations is essential if you wish to submit another manuscript to the journal in the future.

The final topic discussed was rigor and reproducibility. Journals like JCB play a major role in ensuring high-quality and accurate manuscripts are published. This requires an intricate system for detecting fraud and reporting materials and methods, author information, ethical compliance, and data deposition. JCB uses a plagiarism detection software to screen for similar text and an image analyzer to identify any duplications or evidence of manipulation; however, not all journals have the resources to do this. With advances in AI, detecting fraud is becoming faster and more accessible. For example, a software now exists that can screen for duplicate images throughout the literature, a task that was nearly impossible just a few years ago. Additionally, JCB requires authors to make their raw data available upon request, allowing editors to confirm whether the data reported is sound and analyzed properly.

Submitting a paper for publication is a rigorous and demanding process for both the writers and journal editors. By understanding the editor’s perspective, you can navigate this journey with greater clarity and avoid unnecessary confusion. Getting involved in the peer review process early in your career can help you identify unanswered questions in your field to guide your research. A comprehensive understanding of the publication process will increase your chances of successfully publishing your work and contributing to the advancement of science.

This article was edited by Senior Editor Joycelyn Radeny.